Supply Chains Improve, But Labor Lags

Construction firms continue to struggle to find workers.

The supply chain for some construction materials improved markedly during 2022. But there are still several bottlenecks that may throw off the completion date for many projects.

The biggest supply challenge may be labor, not materials. Construction firms continue to report difficulty filling positions and finding subcontractors willing to bid on projects because they already have more work than workers to execute them.

In its 2023 Construction Hiring and Business Outlook survey, conducted with Sage, the Associated General Contractors of America found that 80% of the more than 1,000 respondents reported having a hard time filling some or all positions, compared to only 8% that reported no difficulty. (The remainder had no openings.) The majority — 58% — expect it will be as hard or harder to fill positions over the coming 12 months.

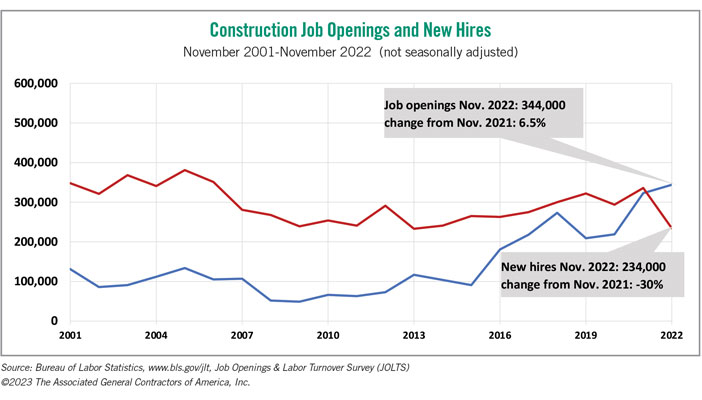

These findings are consistent with employment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). On January 4, it reported that construction industry job openings at the end of November were the highest total for that month in the 22-year history of the series. The 344,000 openings at the end of November 2022 exceeded the 234,000 employees hired during the entire month by nearly 50%, implying that contractors wanted to hire 2.5 times as many workers as they were able to find. (see chart) This hiring gap actually worsened in late 2022, even as homebuilding turned sharply lower and other sectors of the economy slowed their hiring.

There has been widespread improvement in the supply chain for many materials. Waiting times at ports were back to a more typical 24 hours or less by January of this year as compared to early 2022 when more than 100 containerships waited to unload outside of Long Beach and Los Angeles. Similarly, normal (if less eye-catching) vistas have replaced the mountains of containers and trailers waiting to be moved inland or unloaded at already glutted warehouses. Production and shipping times are close to pre-pandemic “normal” levels for lumber and various types of steel used in construction.

Not everything is copacetic on the supply side, however. Materials as diverse as concrete, electrical equipment and semiconductors remain problematic.

The Portland Cement Association reported in October that 43 states were experiencing “tight supplies” of cement. In addition, supplies of fly ash and slag — residues from burning coal that are sometimes used to replace or add to portland cement (the most common type used in construction) when making ready-mixed concrete — have been shrinking as coal-fired power plants shut down. While there may be limited additions to domestic cement production and a possible expansion of imports, many contractors are likely to find that they are put on allocation (receiving only a fraction of previous deliveries) or are shut out altogether in certain regions.

Two types of essential electrical products have experienced ever-lengthening delivery times. One maker of switchgear reported in May that its lead times had doubled from 20 weeks to 40 weeks since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine three months earlier. By December, lead times had reportedly doubled again. Meanwhile, some local electrical utilities have warned contractors that they won’t have enough transformers to allow hookups from the street to new buildings. Lead times for larger or custom transformers that contractors install have reportedly stretched past two years.

Shortages of semiconductors for new vehicles have been well publicized; reports indicate that these have eased in recent months. But semiconductors are also vital components of construction machinery, “smart tools,” and a myriad of building systems and equipment. With orders for each of these types of chips being so much smaller than for vehicles, availability of the specialized chips can be spotty.

In short, many developers will find getting a project to market will be easier than during the past three years. But there are likely to be unpleasant surprises regarding some completion dates, for a variety of reasons.

Ken Simonson is the chief economist with the Associated General Contractors of America. He can be reached at ken.simonson@agc.org.