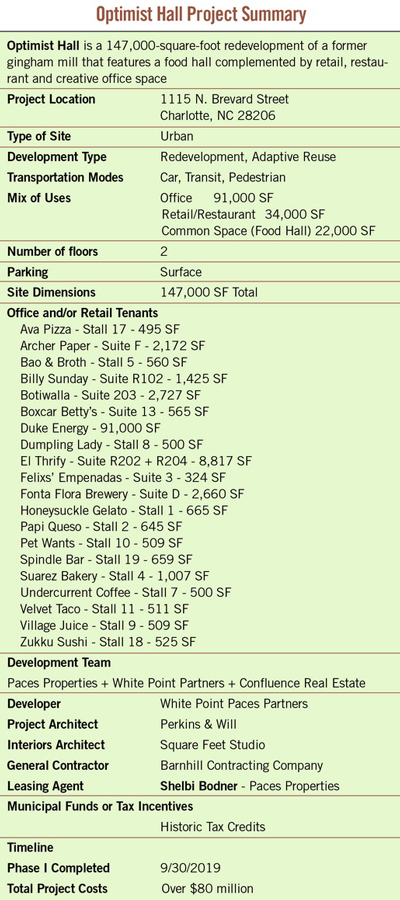

At Optimist Hall, Things are Looking Up

An adaptive-reuse project in North Carolina showcases the appealing possibilities of older industrial buildings.

There’s cause for confidence in Charlotte’s burgeoning Mill District, where the cheerily named Optimist Hall is the latest revitalization of a turn-of-the-century textile mill. The adaptive-reuse project adds a 22,000-square-foot food hall, 34,000 square feet of restaurant and outdoor space, and 91,000 square feet of office space to an increasingly vibrant neighborhood that faced dire prospects after the U.S. textile industry collapsed near the end of the 20th century.

A collaboration between Charlotte’s White Point Partners and Atlanta’s Paces Properties, Optimist Hall occupies the former Highland Park Manufacturing Company’s Mill No. 1. Once one of the nation’s largest gingham manufacturers, the facility was built and expanded between 1892 and 1930. The U-shaped structure houses the food hall in the east wing of its main level, restaurant and retail space in its west wing (along with a few lower-level spaces) and Duke Energy offices above.

Erik Johnson, co-founder of White Point Partners, had worked with Merritt Lancaster of Paces Properties previously when he was a banker and Lancaster was a multifamily housing operator. They decided to join forces once again to refurbish an old structure in Charlotte. Lancaster, who helped develop Atlanta’s Krog Street Market food hall with Paces Properties, had an interest in replicating something similar in North Carolina’s largest city — and he saw an opportunity as well.

“We compared the food scene in Charlotte to Charleston, Atlanta and Nashville and observed there was less competition,” he said.

They were looking for a historic property from the start. Johnson said White Point Partners focuses on reusing historic buildings because they supply character that can’t be replicated. Their search covered the Charlotte area and wasn’t focused exclusively on the Mill District, but it proved a logical fit.

“It wasn’t so much that we chased that market, but that’s what was open,” Johnson said.

An Area on the Rebound

Formerly a center of the textile industry, the Mill District stretches north of Charlotte’s downtown, starting just across Interstate 277 from the city’s business center and spanning a sliver about three miles long. It contains seven intact mills built between 1889 and 1940. Local textile tycoon Daniel A. Tompkins developed many of them, including the precursor to Optimist Hall. Tompkins built more than 250 cotton oil mills, 150 electric plants and 100 textile mills across the South before he died in 1914.

The local textile industry and the surrounding neighborhoods began a long decline after World War II. Statistics from the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Commission show how dire things became. As recently as 1987, more than 97% of the housing units in Optimist Park, the small historic neighborhood that surrounds the hall, were deemed dilapidated or deteriorated.

Fortunes have turned in the past decade, however. The neighborhood is attracting young professionals who are renovating the housing stock, and the long-shuttered mills have been repurposed or are in various stages of redevelopment. Highland Park Mill No. 3 is now Heist Brewing and Highland Mill Lofts. The Alpha Cotton Mill is now Alpha Mill Apartments. The Mecklenburg Cotton Mill is The Lofts at NoDa Mills. The Louise Cotton Mill is now The Lofts at Hawthorne Mill. The Chadbourn Hosiery Mills sold in August to a group planning an office and retail conversion. A final historic structure, the Johnston Mill, is expected to be developed into apartments.

A supply of historic buildings wasn’t the only incentive for the developers of Optimist Hall. The city’s recent Lynx Blue Line light rail extension runs alongside the project, and a station is located a quarter mile away from Optimist Hall.

The courtyard at Optimist Hall features plentiful outdoor seating and views of Charlotte's downtown skyline a short distance to the south. The Plaid Penguin

Despite its name, the Mill District is not merely industrial — or all mill conversions, either. It contains industrial parcels along with a large residential population, especially near the Optimist Hall portion. One element it did not contain was offices.

“A lot of people said ‘this is not an office market — how are you going to lease office space?’ ” Johnson said.

Standard market analysis showed that the demographics of the area weren’t ideal, but its central location and proximity to light rail, along with plenty of housing nearby (there are 1,200 to 1,500 apartment units within a half mile of the property), helped sway the decision to add office space.

Lancaster added that the neighborhood didn’t quite match the stereotypical millennial demographic ideal of the food hall market, either — but that was OK with the development team.

“If you end up in a market that’s too highly focused on the modern apartment dweller, that’s just a sliver of the market,” he said.

The Mill District is more affordable and mixed.

“It’s much more diverse, and you have a good mix of single-family housing and rental housing, and for us that’s a very important thing,” Lancaster said. “We like to be in neighborhoods where someone could spend their whole life.”

A Lot of Work, and Surprises

Optimist Hall wasn’t much to look at when the project began in 2014. Bricked-over windows covered the façade, and barbed wire surrounded the property.

“The west wing was a pretty scary space,” Lancaster said. “It looked like it could be the backdrop to a horror movie.”

There were lots of problems endemic to historic structures.

There had been a partial fire at some point, a significant amount of rot, and the sub-flooring required a lot of work. Some structural supports were a source of concern. Removing brick from the windows prompted worries about undermining the building’s structure. Internal wooden structural beams had to be replaced with steel in several places.

“It’s an old mill, and we found all sorts of surprises,” Lancaster said. “It was interesting to disassemble and reassemble.”

A cryptic surprise was an immense locked safe, a relic of the building’s past that will live on.

“It will sit there and be a mystery,” Lancaster said. “I don’t think it’s been moved. It weighs about 1,500 pounds”

Overall, though, the fundamentals of the structure were extremely sound.

“You couldn’t really tell from the outside, but when we saw the old building from the inside, the bones were all still there,” Lancaster said. “The floor is so thick. It’s built out of hard pine. I think it’s got the fire rating of a steel building.”

The old building required modern insertions such as HVAC and electrical infrastructure, which developers worked to confine to the crawl space.

Challenging Financing

The renovation of Optimist Hall might have been fairly straightforward, but paying for it was not.

“Capital-wise, it’s the most complicated deal I’ve ever been involved with,’’ said Johnson, noting that it required work with the City of Charlotte, Mecklenburg County and national authorities. Financing involved common equity, preferred equity, a mezzanine loan, a senior loan, federal historic tax credits, state historic tax credits and a bridge loan.

"Mr. Tompkins designed this building to bring in a lot of natural light," said Holden Spaht, an architect at Square Feet Studios who worked on the interior of Optimist Hall. "We wanted to make sure we didn't cover up any of those windows." The Plaid Penguin

The Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives Program, also called the Federal Historic Tax Credit program, gives a 20% federal tax credit to property owners who substantially rehabilitate a historic commercial building for income-producing uses. North Carolina offers a 10% historic state tax credit for properties that qualify for the federal tax credit and cost between $10 million to $20 million to develop. And the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission offers a 50% property tax deferment for qualifying historical properties.

In the end, it cost $12 million to acquire the property, and the process involved buying 30 different land parcels from 28 different owners — one of whom was incarcerated at the time.

“Yes, we even had to go to jail for a signature,” Johnson said.

Tenants Line Up

While financing was complicated, attracting a major office tenant in Duke Energy was the easy part of the process. The historic and distinctive quality of the building offered something different from most suburban or downtown spaces in the Charlotte market.

“Duke Energy is focused on employee retention,” Lancaster said. “But if you’re working downtown, nobody gets out of a 40-story building.”

An environment different from the glassy corporate-tower confines of city center was just what some employees wanted most.

“We’ve been told there were employees who lobbied Duke Energy to work in this location,” he said.

In fact, he said Optimist Hall had more office suitors than it could accommodate, because the developers weren’t going to expand beyond the historic building’s footprint.

“We showed it to companies who said they needed the ability to expand, and we couldn’t give them that,” Lancaster said.

Food hall tenanting was a different story. It was a relatively new format for the Charlotte market, and it was in an unconventional location. Like holding a party, it requires a sense that a few desirable guests must show up to attract anyone at all.

“You get the first people to sign on, and then you can get everyone on board,” Lancaster said. “It can be a terrible feeling when you have 30,000 feet of restaurant space and you haven’t filled it. Once we had a couple of people that were circling, that’s when we could breathe.”

Lancaster stressed that they weren’t looking for just any tenants.

“We’re very selective,” he said. “We don’t put signs up and wait for people to come down. We spent a lot of time and energy researching and getting the best local chefs we can get. Sometimes we had to go out of the market.”

Currently, 16 of 19 spaces in the food hall are leased, as are seven of nine commercial slots elsewhere in the building. Tenants include the first local location of Atlanta-based Honeysuckle Gelato, the second location of Chicago cocktail bar Billy Sunday, the third location of Winston-Salem’s Village Juice Company, the first local outlet for Charleston-based fried chicken chain Boxcar Betty, the first Charlotte branch of Dallas-based Velvet Taco, and the first Charlotte location of Atlanta-based Archer Paper Goods.

Some local businesses are expanding here, including Undercurrent Coffee, Suarez Bakery and others. Fonta Flora Brewery is located in the lower east wing.

Interior Design That Aimed to be ‘Respectful’

The design of the food hall spaces, including the stall layout and the courtyard dining area, was entrusted to Atlanta’s Square Feet Studios. Holden Spaht, an architect at Square Feet Studios, noted that they wanted to be respectful of the building’s history while creating an engaging food hall. They commenced after work on the historic envelope wrapped up.

“We were brought in after a lot of the historic-preservation nuts and bolts had been worked out,” Spaht said. “They conceived of the food hall as a set of interventions that operated within that field.”

The most important renovation task, Spaht explained, was to respect the integrity of the building’s 100-year-old shell.

“Mr. Tompkins designed this building to bring in a lot of natural light,” Spaht said. “We wanted to make sure we didn’t cover up any of those windows.”

By the same measure, the renovation was unique in that the building was originally designed to accommodate massive textile looms, not humans.

“Originally, the building had been scaled to the machinery,” Spaht said. “We scaled the environment to the individual without intervening in the design much at all.”

All food stalls are in the middle of the space, with the only exceptions being a common bar and some stalls that line the partition between the food hall and the Duke Energy space. That also was designed with care, Spaht explained.

“It doesn’t feel like a wall; it feels like a porous edge,” he said.

The stalls were also created to have a light footprint.

“They feel like they’ve been inserted under the shell of a historic building with a very light touch,” Spaht said. “They’re not attached. The additions were designed with low impact in mind. It doesn’t ask the building to do anything that it wasn’t already doing.”

He explained other solutions:

“Picnic tables made of reclaimed heart pine factory flooring integrate with an overhead armature to create smaller dining spaces within the larger building,” Spaht said. “Repurposed old factory windows found in the basement, along with light-translucent woven scrims, create partition screens around intimate 8-foot-by-8-foot ‘micro lounges,’ utilizing the building’s original structural modules that were designed to fit common weaving and spinning equipment of the time. Decorative lighting in the food hall is entirely composed of reclaimed factory pendants, also found in the basement. They were rewired but otherwise largely left in their found and aged condition.”

New ductwork was painted to match the historic palette of the building.

The courtyard plan features 16 8- to 9-foot-tall magnolia trees planted in herringbone-patterned wood planter boxes. Cypress and painted metal furniture appears in this space.

‘A Testament to Their Quality’

Dan Morrill, consulting director of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, praised the work at Optimist Hall.

“They did a good job,” he said. “It was a sensitive job.”

Morrill pointed out that the idea these structures had any utility is fairly recent.

“When I first got involved in preservation work here, none of the old mills had been converted,” he said. “Some of them were in use, some were used as warehouses, and some were empty.”

Ironically, the fact that the Mill District wasn’t of much interest to anyone turned out to be a boon to its historic architecture.

“There are some mills that have been lost, but what’s really striking is how many remain, which is a testament to their quality,” Morrill said. “If you leave them alone, they just sit there and wait for someone to do something to them. They’re very well constructed.”

Their location next to rail lines was once ideal for shipping products. Now it’s ideal for moving humans on the light rail extension. Their expansive floor plans also lend themselves to nearly any use.

“They’re so easily convertible because you’ve got these large expanses of open space that can easily be divided by partition walls into offices, condominiums, lobbies and anything you’d like,” Morrill said.

While quality tenants are obviously essential, the key to the success of a food hall is not that any individual tenant is the destination but rather the full venue itself.

“In a perfect world, the experience of being there is your favorite part, not picking pizza or sushi or such,” Lancaster said. “People go to Optimist because they want to go to Optimist, not because of a specific thing.”

The food hall has been booming thus far, Lancaster observed.

“They are very busy — I’m not sure operators fully expected it,” he said.

This bet on a formerly shuttered site appears to be paying off. It’s revitalized a historic property while providing occasion for profit.

“You’ve got that character that people will pay extra for,” Johnson said. “We’re doing this to make money, but we’re also excited about doing something for the community.”

Anthony Paletta is a freelance writer based in New York.